In ReactiveX an observer subscribes to an Observable. Then that observer reacts to whatever item or sequence of items the Observable emits. This pattern facilitates concurrent operations because it does not need to block while waiting for the Observable to emit objects, but instead it creates a sentry in the form of an observer that stands ready to react appropriately at whatever future time the Observable does so.

This page explains what the reactive pattern is and what Observables and observers are (and how observers subscribe to Observables). Other pages show how you use the variety of Observable operators to link Observables together and change their behaviors.

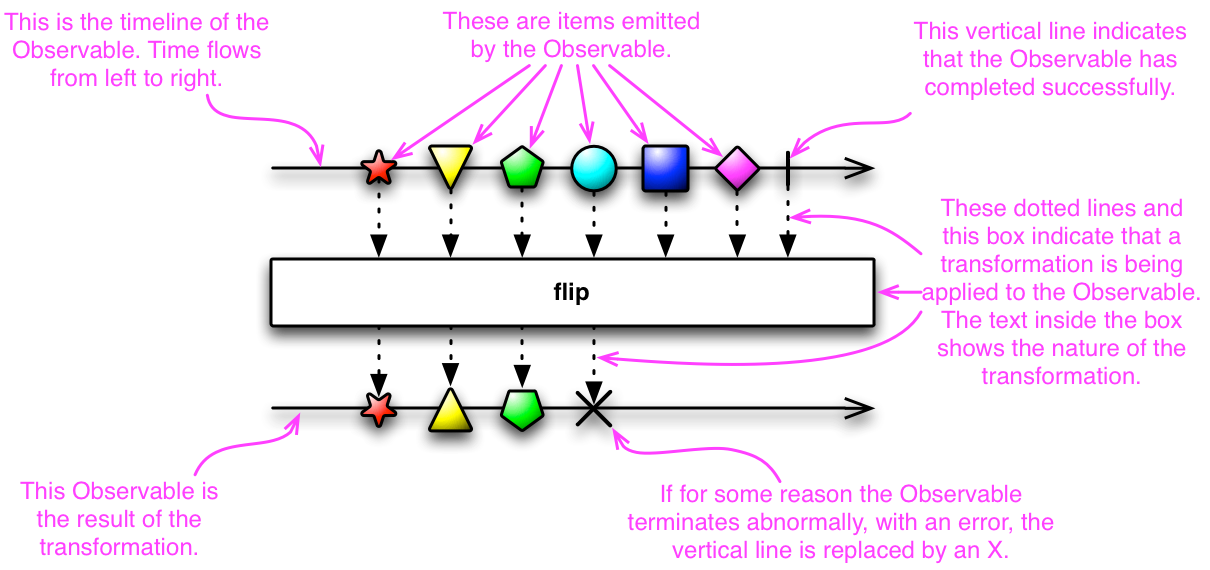

This documentation accompanies its explanations with “marble diagrams.” Here is how marble diagrams represent Observables and transformations of Observables:

In many software programming tasks, you more or less expect that the instructions you write will execute and complete incrementally, one-at-a-time, in order as you have written them. But in ReactiveX, many instructions may execute in parallel and their results are later captured, in arbitrary order, by “observers.” Rather than calling a method, you define a mechanism for retrieving and transforming the data, in the form of an “Observable,” and then subscribe an observer to it, at which point the previously-defined mechanism fires into action with the observer standing sentry to capture and respond to its emissions whenever they are ready.

An advantage of this approach is that when you have a bunch of tasks that are not dependent on each other, you can start them all at the same time rather than waiting for each one to finish before starting the next one — that way, your entire bundle of tasks only takes as long to complete as the longest task in the bundle.

There are many terms used to describe this model of asynchronous programming and design. This document will use the following terms: An observer subscribes to an Observable. An Observable emits items or sends notifications to its observers by calling the observers’ methods.

In other documents and other contexts, what we are calling an “observer” is sometimes called a “subscriber,” “watcher,” or “reactor.” This model in general is often referred to as the “reactor pattern”.

This page uses Groovy-like pseudocode for its examples, but there are ReactiveX implementations in many languages.

In an ordinary method call — that is, not the sort of asynchronous, parallel calls typical in ReactiveX — the flow is something like this:

Or, something like this:

// make the call, assign its return value to `returnVal` returnVal = someMethod(itsParameters); // do something useful with returnVal

In the asynchronous model the flow goes more like this:

Which looks something like this:

// defines, but does not invoke, the Subscriber's onNext handler

// (in this example, the observer is very simple and has only an onNext handler)

def myOnNext = { it -> do something useful with it };

// defines, but does not invoke, the Observable

def myObservable = someObservable(itsParameters);

// subscribes the Subscriber to the Observable, and invokes the Observable

myObservable.subscribe(myOnNext);

// go on about my business

The Subscribe method is how you connect an observer to an

Observable. Your observer implements some subset of the following methods:

onNextonErroronNext or onCompleted.

The onError method takes as its parameter an indication of what caused the error.onCompletedonNext for the final time, if it has not

encountered any errors.

By the terms of the Observable contract, it may call onNext zero or

more times, and then may follow those calls with a call to either onCompleted or

onError but not both, which will be its last call. By convention, in this document, calls to

onNext are usually called “emissions” of items, whereas calls to

onCompleted or onError are called “notifications.”

A more complete subscribe call example looks like this:

def myOnNext = { item -> /* do something useful with item */ };

def myError = { throwable -> /* react sensibly to a failed call */ };

def myComplete = { /* clean up after the final response */ };

def myObservable = someMethod(itsParameters);

myObservable.subscribe(myOnNext, myError, myComplete);

// go on about my business

In some ReactiveX implementations, there is a specialized observer interface, Subscriber, that

implements an unsubscribe method. You can call this method to indicate that the Subscriber is no

longer interested in any of the Observables it is currently subscribed to. Those Observables can then (if they

have no other interested observers) choose to stop generating new items to emit.

The results of this unsubscription will cascade back through the chain of operators that applies to the Observable that the observer subscribed to, and this will cause each link in the chain to stop emitting items. This is not guaranteed to happen immediately, however, and it is possible for an Observable to generate and attempt to emit items for a while even after no observers remain to observe these emissions.

Each language-specific implementation of ReactiveX has its own naming quirks. There is no canonical naming standard, though there are many commonalities between implementations.

Furthermore, some of these names have different implications in other contexts, or seem awkward in the idiom of a particular implementing language.

For example there is the onEvent naming pattern (e.g. onNext,

onCompleted, onError). In some contexts such names would indicate methods by means of

which event handlers are registered. In ReactiveX, however, they name the event handlers themselves.

When does an Observable begin emitting its sequence of items? It depends on the Observable. A “hot” Observable may begin emitting items as soon as it is created, and so any observer who later subscribes to that Observable may start observing the sequence somewhere in the middle. A “cold” Observable, on the other hand, waits until an observer subscribes to it before it begins to emit items, and so such an observer is guaranteed to see the whole sequence from the beginning.

In some implementations of ReactiveX, there is also something called a “Connectable” Observable. Such an Observable does not begin emitting items until its Connect method is called, whether or not any observers have subscribed to it.

Observables and observers are only the start of ReactiveX. By themselves they’d be nothing more than a slight extension of the standard observer pattern, better suited to handling a sequence of events rather than a single callback.

The real power comes with the “reactive extensions” (hence “ReactiveX”) — operators that allow you to transform, combine, manipulate, and work with the sequences of items emitted by Observables.

These Rx operators allow you to compose asynchronous sequences together in a declarative manner with all the efficiency benefits of callbacks but without the drawbacks of nesting callback handlers that are typically associated with asynchronous systems.

This documentation groups information about the various operators and examples of their usage into the following pages:

Create, Defer, Empty/Never/Throw,

From, Interval, Just, Range, Repeat,

Start, and TimerBuffer, FlatMap, GroupBy, Map, Scan, and

WindowDebounce, Distinct, ElementAt, Filter,

First, IgnoreElements, Last, Sample,

Skip, SkipLast, Take, and TakeLastAnd/Then/When, CombineLatest, Join,

Merge, StartWith, Switch, and ZipCatch and RetryDelay, Do, Materialize/Dematerialize,

ObserveOn, Serialize, Subscribe, SubscribeOn,

TimeInterval, Timeout, Timestamp, and UsingAll, Amb, Contains, DefaultIfEmpty,

SequenceEqual, SkipUntil, SkipWhile, TakeUntil,

and TakeWhileAverage, Concat, Count, Max, Min,

Reduce, and SumToConnect, Publish, RefCount, and ReplayThese pages include information about some operators that are not part of the core of ReactiveX but are implemented in one or more of language-specific implementations and/or optional modules.

Most operators operate on an Observable and return an Observable. This allows you to apply these operators one after the other, in a chain. Each operator in the chain modifies the Observable that results from the operation of the previous operator.

There are other patterns, like the Builder Pattern, in which a variety of methods of a particular class operate on an item of that same class by modifying that object through the operation of the method. These patterns also allow you to chain the methods in a similar way. But while in the Builder Pattern, the order in which the methods appear in the chain does not usually matter, with the Observable operators order matters.

A chain of Observable operators do not operate independently on the original Observable that originates the chain, but they operate in turn, each one operating on the Observable generated by the operator immediately previous in the chain.